tldr

As a trainee GP, even the most common presentation of chest pain can make you think. Am I asking the right questions to help me treat this patient?

I believe that medical education should make better use of Venn diagrams, medical statistics (especially positive predictive value) and risk scores to improve the teaching of undifferentiated presentations. So that people can more quickly memorise the really specific questions that help to make a diagnosis from a list of differentials.

I am currently training to be a GP in the UK and part of my training involves working in the Emergency Department (ED). I absolutely love it and part of that is because the job I am doing is completely relevant to my future career that I want to do.

Both ED/EM doctors and GPs work with new patients, who present with new problems. This is called “the undifferentiated patient/disease”. These patients can have almost any symptom, sign or disease and its your job to work out as efficiently as possible what it is, that is causing them the issue.

To be good at this job requires either a lot of experience or a good diagnostic mind and clinical acumen. I am doing my best to improve both of these!

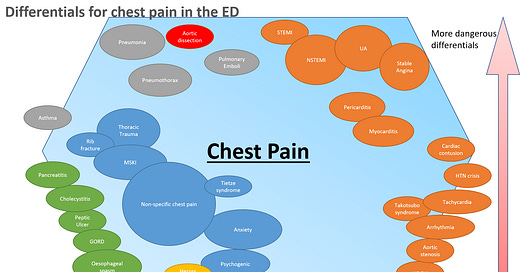

The most common presentation you will see in a UK ED is “chest pain”, not heart attack or MI or STEMI or CABG or PE or rib fracture but chest pain. “Chest pain” is the undifferentiated symptom cluster. It is the very large group of people that could have a life threatening condition that must be treated in minutes or absolutely nothing physically wrong with them at all.

Last week, I was seeing one of these patients and I started thinking (a novel change I know!) about the pattern that I had fallen into. Was I following the right pattern in my assessment? Essentially, was I asking the right questions to these patients with chest pain? Or was I just reeling off a list of questions that I had memorised? Was I using a scattergun approach or did I have a systematic approach to ruling In or Out disease?

The Bread and Butter Topic

As doctors, we like to think that chest pain is one of our bread and butter topics. I have been studying medicine for over a decade. I have received hundreds, if not thousands of hours of lectures and workshops. I have received small group teaching sessions from world class experts of cardiovascular physiology. I have read textbooks. I have been involved in simulation training. I have listened to hours of podcasts. I have passed numerous written exams, essays, OSCEs and other assessments. I have examined and assessed hundreds of patients with chest pain. By rights, after all of this teaching and learning and experience, I should be pretty good at dealing with patients with chest pain.

As far as I know, I have never missed a serious case of chest pain and I know for a fact that I have stopped/ relieved a few heart attacks with the quick application of Aspirin and MONAC (see previous article…)

But when I finished with that patient last week, I just had this nagging thought in my head, that maybe I didn’t know quite as much as I should do. I thought I would be able to put my thoughts down on paper and quickly improve my own learning but also produce something that others would find useful.

I then started thinking more and more about how we learn about chest pain and ACS and it took my down a rabbit hole that ended about 20 hours later!

The Gold Standard Teaching of Medicine

There are many ways to teach medicine based on different goals, different personalities and different educational theories. It is hard to really argue if one approach is any more efficient than any other, but here goes anyway..

The classical method is a mix of: a textbook definition; a list of symptoms, signs and investigations; an eminent expert and powerpoint slides. This approach tends to be didactic, involve rote learning and large volumes of information. Traditionally it also tended to be focused solely on one disease eg. STEMI or PE or aortic dissection.

When I was at medical school, my university was using the “systems approach” to teaching which involved indepth lectures on “the cardiovascular system” or “the respiratory system” and then explaining how the organ works and building up the jigsaw pieces to explain how the diseases occur and what symptoms they present with and why. The idea behind this method is that a scientifically grounded doctor will be able to work out the cause of the symptoms from first principles.

Both of these methods leave you, the student doctor, with a long list of possible questions that you could ask about the symptoms for that specific disease or symptom. There was very little focus on teaching you, what are the most important questions to ask about this presentation?

A relatively recent invention that has sprung from EBM (evidence based medicine) is the idea of a “risk score”. These scores have been used to better classify and define how a disease presents, so that we can then be more statistically sure that we are giving the right treatment to the right group of patients.

These risk scores are models or checklists, that have been created and then tested. Some of these scores just take a few of the symptoms and signs out of a textbook, put a checkbox next to them and then add them up to equal the full definition. Some of these scores have been more cleverly created where studies were conducted to diagnose patients and then ask what symptoms they presented with. Some scores involve the text book list of symptoms but then have a different number of points for each criteria (a weighted score) and some scores have used AI magic to come up with odd mathematical scores.

The point of discussing this, is that if these scores have been shown to work and to improve the treatment of patients, then surely the most efficient approach would be to just teach people to use these scores as their diagnostic tools?

There are a number of issues with just teaching the scores. Firstly, some scores rely on the clinician to already have experience or knowledge of the presentation to be able to add points to the score, so no good if you don’t already have the expected knowledge. Second, these scores are by their nature quick and simple, which means they do not always mention information that may be relevant. Third, these tests may “work” but we do not know if maybe a different combination of signs or symptoms or weighting may “work better”. And lastly, there are a large number of scores that all have slight variation and therefore, only teaching one or two scores may not do the topic justice.

My new approach

“There is nothing new under the sun”, however, this approach is new to me and I expect may be novel/unusual for other people as well.

I propose that the way we teach medicine should be altered to include the following techniques:

Firstly, it is important to work from first principles and the most basic of them all is medical statistics. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), prevalence. Without having a basic understanding of these concepts you can not really understand how modern medicine works.

https://geekymedics.com/sensitivity-specificity-ppv-and-npv/ - I can not explain medical statistics any better than these guys already have.

Secondly, the concept of Bayes’ theorem and the pre- and post-test probability of a diagnosis. This can be summarised as, if this patient tells me they have chest pain and if I ask them about vomiting, will this increase or decrease the likelihood that they are having a heart attack? As opposed to asking them if they also have a rash?

I believe it is important to understand this concept and use it to cut down unnecessary questions. Think of it as a scalpel cutting away unnecessary words that do not help you rule in or out a differential. You need to work from the background epidemiology of the symptoms step by step to the most likely diagnosis.

The following diagram is an excellent example of this principle in operation:

https://ebm.bmj.com/content/18/2/80

Thirdly, I believe that it is important for people to learn medicine by learning from the real world. I believe we should focus more of our teaching on “undifferentiated presentations” and symptom clusters rather than on teaching “diseases”. I believe we should focus our teaching on how “patients’ present” and not what the textbook definition of a disease is. This may just be my inner trainee GP talking but for me its far more important to be able to guide a patient down roughly the right investigative/ referral pathway towards the right eventual diagnosis than to be able to know thousands of conditions off the top of my head but not be able to make a diagnostic plan efficiently.

We should start by teaching how patients present, then the underlying principles of what causes those symptoms and why they occur and then what the disease definitions are at the end.

Fourthly, we underuse Venn diagrams in medicine. The Venn diagram is almost the perfect technique for teaching about differential diseases because it can be used to demonstrate where these diseases are similar and where they are different which is the core skill of the diagnostician.

Fifthly, I believe we should use the “risk score” approach to re-write the textbooks and the lectures slides and the disease definitions. I believe that we should list a disease symptoms and signs in a standardised way. Each disease definition should have the most common symptoms, the symptoms with the highest PPV (highest weighted, most differential, most sensitive) and the best NPV symptoms. Rather than just listing symptoms in a classical order, or alphabetical or anatomical. These should be listed in how useful those criteria are for either ruling in or ruling out the disease.

My experiment with improving the history taking of chest pain

I have tried to put these principles into action for the sake of improving my history taking for chest pain and improving my diagnosis of ACS.

I have re-read the Oxford Handbook of Clinical Medicine chapter on ACS and the Acute Medicine chapter and The Symptom Sorter by Hopcroft. I have also reviewed the Acute Cardiovascular Care Association guidance and papers on risk scoring in GP and ED (HEART, T-MACS, EDACS, GRACE, TIMI, Gencer, Marburg Heart Score, INTERCHEST, Grijseels and Bruins Slot). I have also read a few other papers on chest pain management and ACS diagnosis. All of this was absolutely fascinating and made me realise just how little of medicine that I really know.

I have attempted to summarise all of the points raised within these different frame works into one comprehensive list of high risk information that should be assessed by a clinician with a patient in chest pain to rule in or out a diagnosis of ACS.

I have tried to weight the questions by choosing the highest weighted score from each of the different criteria. Obviously, this means that what I have put together has no real value because it is a mish mash and not validated but my overall aim was to try and show that some questions are more important to ask than others. I also wanted to show that some clinicians or previous studies have put more faith in certain symptoms than others and that using this pre-weighted experience may prove beneficial.

I intend to continue to develop this model and thinking for various other presentations and diseases over the next few years because I believe this approach is worthwhile for making myself a better clinician but also because I want to be able to teach others to be better doctors that I am and in a much more efficient manner.

For the full slide pack, that shows the working behind these two slides please use the following link that shows each of the scores and their criteria.

https://www.slideshare.net/JakeMatthews12/improving-the-teaching-of-chest-pain-and-acs

“Finally, it is more complicated than that! Always remember what Algernon would have said in Oscar Wilde's unwritten play ‘The importance of being evidence-based’: The evidence is rarely pure and never simple. Modern life would be very tedious if it were either, and science-based healthcare a complete impossibility.”

https://ebm.bmj.com/content/18/1/5#xref-ref-8-1

References

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/2048872619885346

The OHB of Acute Medicine

The OHB of Clinical Medicine

https://www.bmj.com/content/340/bmj.c1269

https://qualitysafety.bmj.com/content/21/2/160?ijkey=c7f17e055c823c4b9a23ad855dc78edf24f8e905&keytype2=tf_ipsecsha

https://ebm.bmj.com/content/18/1/5#xref-ref-8-1

https://ebm.bmj.com/content/18/2/80

https://academic.oup.com/nop/article/2/4/162/2460002

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4389891/

https://www.annemergmed.com/article/S0196-0644(18)31529-4/fulltext

Understanding diagnostic tests 1: sensitivity, specificity and predictive values. Akobeng AK. Acta Paediatr. 2007 Mar; 96(3):338-41

Harskamp RE, Laeven SC, Himmelreich JC, Lucassen WAM, van Weert HCPM. Chest pain in general practice: a systematic review of prediction rules. BMJ Open. 2019 Feb 27;9(2):e027081. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027081. PMID: 30819715; PMCID: PMC6398621.

Va Den Berg P, Burrows G, Lewis P, Carley S, Body R. Validation of the (Troponin-only) Manchester ACS decision aid with a contemporary cardiac troponin I assay. Am J Emerg Med. 2018 Apr;36(4):602-607. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2017.09.032. Epub 2017 Sep 23. PMID: 29079376.

Body R, Morris N, Reynard C, Collinson PO. Comparison of four decision aids for the early diagnosis of acute coronary syndromes in the emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2020 Jan;37(1):8-13. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2019-208898. Epub 2019 Nov 25. PMID: 31767674.

https://academic.oup.com/fampra/article/28/3/323/484517

https://www.mdcalc.com/interchest-clinical-prediction-rule-chest-pain-primary-care

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2832616

https://www.mdcalc.com/timi-risk-score-ua-nstemi

https://www.mdcalc.com/grace-acs-risk-mortality-calculator

https://www.mdcalc.com/emergency-department-assessment-chest-pain-score-edacs

https://www.mdcalc.com/troponin-manchester-acute-coronary-syndromes-t-macs-decision-aid

Six AJ, Backus BE, Kelder JC. Chest pain in the emergency room: value of the HEART score. Neth Heart J. 2008;16(6):191-6.

•Backus BE, Six AJ, Kelder JC, et al. Chest pain in the emergency room: a multicenter validation of the HEART Score. Crit Pathw Cardiol. 2010;9(3):164-9.

•Backus BE, Six AJ, Kelder JC, et al. A prospective validation of the HEART score for chest pain patients at the emergency department. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168(3):2153-8.

•Stopyra JP, Riley RF, Hiestand BC, et al. The HEART Pathway Randomized Controlled Trial One Year Outcomes. Acad Emerg Med. 2018;

•Ljung L, Lindahl B, Eggers KM, et al. A Rule-Out Strategy Based on High-Sensitivity Troponin and HEART Score Reduces Hospital Admissions. Ann Emerg Med. 2019;73(5):491-499.

•Mahler SA, Riley RF, Hiestand BC, et al. The HEART Pathway randomized trial: identifying emergency department patients with acute chest pain for early discharge. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2015;8(2):195-203.

•Nieuwets A, Poldervaart JM, Reitsma JB, et al. Medical consumption compared for TIMI and HEART score in chest pain patients at the emergency department: a retrospective cost analysis. BMJ Open. 2016;6(6):e010694.

•Poldervaart JM, Langedijk M, Backus BE, et al. Comparison of the GRACE, HEART and TIMI score to predict major adverse cardiac events in chest pain patients at the emergency department. Int J Cardiol. 2017;227:656-661.

•Poldervaart JM, Reitsma JB, Backus BE, et al. Effect of Using the HEART Score in Patients With Chest Pain in the Emergency Department: A Stepped-Wedge, Cluster Randomized Trial. Ann Intern Med. 2017.

https://www.mdcalc.com/marburg-heart-score-mhs

•Gencer B, Vaucher P, Herzig L, et al. Ruling out coronary heart disease in primary care patients with chest pain: a clinical prediction score. BMC Med. 2010;8:9. Published 2010 Jan 21. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-8-9