No 60 - "How Doctors Think", a book review

How Doctors Think by Dr Jerome Groopman, American Oncologist was published in 2008. The title explains it all. It is a very well written book on the science of medical decision making. It uses interesting and confusing clinical cases from a range of specailities to explain common problems in medicine.

It is a mix of medical detective story, psychology textbook and self help manual. The aim is of the book is to prompt patients to ask the right questions of their doctors, and to prompt clinicians to think through their cases more systematically not to fall into common and easy errors of judgment.

The book consists of 12 chapters, 280 pages and can easily be read within a week. It is not a page turner but is the sort of book you could read for an hour with a coffee and then sit and think about for a few minutes and discuss with a colleague.

Anyone who has read MediCurious before will know they I am obsessed with thinking about how to be the best clinician you can be, and I think this book gives some really helpful points. If you would like similar posts, then see below:

The following points are my summary and take home messages from this book. I would highly recommend that you read the book, but if you don’t have the time then hopefully the following points will give you the gist:

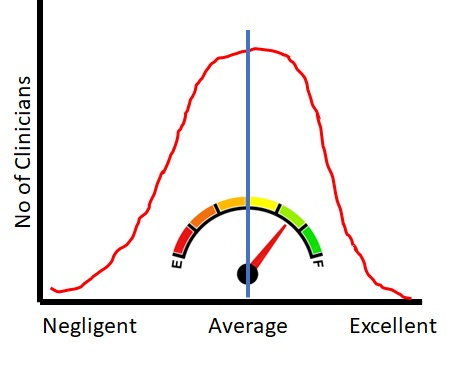

I am hoping that this sketch graph of a bell cure illustrates that any clinician could improve their performance, if they wanted to and that this book may help.

Medicine is hard, biology is complicated, not everyone responds the same. Making medical judgements requires statistical thinking. Making errors in medical judgements is more common than most doctors think and much more complicated than most patients expect.

Almost every aspect of medicine is uncertain. Patients describe symptoms differently, their biology is different, their test results may not be within the "normal range", their tests may be read subjectively by a colleague, their diagnosis could be uncertain, their prognosis is uncertain and only time will tell. Every patient and every consultation is unique.

Most medical mistakes are due to errors in thinking, not errors in technical knowledge.

Most of these errors could be prevented, or caught sooner, if systematic approaches to the consultation are embraced.

Start with the Epilogue and Afterward if you are an experienced clinician.

I would recommend that every doctor read this book. If you are a medical student, then read it before you start clinical medicine. Then read it again after your final exam and before you start work on the wards. Then read it again when you have almost finished your training and you want a reminder to be humble.

If you are a senior clinician and feel like you are stuck in a rut then I think this book could give you a jolt. It may also give you one or two tips to try in consultations.

No 1 lesson from this book, is that compassionate and "good clinicians" stay humble. They question their own thinking, their own knowledge and are curious about their patients.

Second order thinking, you have to ask the obvious questions, order the obvious tests and then THINK "what else?"

The clinical cases in the book are used as parables to explain how different specialities approach a problem, common problems, common errors in thinking and cognitive psychology

Common medical errors, occur because of common ways to think wrongly

Cognitive psychology = "thinking traps"

3As = anchoring + attribution (stereotype) + availability (recent experience) = cured by "what else could it be?"

3cs = communication, critical thinking, and compassion.

Take home lesson = always make a differential list even for the "simplist cases". Forcing yourself to ask "what else could it be?" prevents missed diagnosis. Forcing yourself to think "what is the worst possible cause?" makes sure you ask for red flags or order extra investigations. Following a systematic approach to all cases makes sure you don't miss things - surgical sieve - VITAMIN D.

In theory, most medical errors could be prevented by reducing human error.

Humans are not perfect, even the best consultants can make human errors, which is why we need to build systems that make it difficult to make an error or difficult to miss the obvious.

Common presentations are common areas of error for example, hypochondriacs and regular attenders, women during menopause, women with abdominal pain, the elderly who may be confused - these cases make it easy to fall into bad habits and not to think clearly about new symptoms or unusual symptoms. They are traps and require extra caution, because they are so common.

Other common mistakes - slightly abnormal blood tests that have been ignored for years, becomes habit to ignore them. Like LFTs, or slightly abnormal FBC.

Diagnostic cascade or diagnostic drag, fixation, labelling, = Mis-diagnosis.

Learning styles - visual, stories, lists, mnemonics

Ockham's razor - are all the symptoms explained by one condition? or is the picture complicated by 2 or more conditions?

There are various "cognitive bugs" that can be treated by a "broad spectrum therapy" like keeping an open mind and questioning the thinking process. Do all these symptoms, signs and results fit with the working diagnosis? If they don't fit, could we be missing something?

Patients should be encouraged to ask "what else could it be?"

safeguard against = premature closure, framing, availability bias,

If you hear hoofbeats, think horses not zebras. But sometimes those hoofbeats are not always horses, sometimes they are zebras. Don’t forget that zebras exist!

Sometimes, you should be a zebra hunter.

Thinking errors = falling dominos, leading you down the wrong diagnostic path

No expert can always predict the clinical course, and this should teach clinicians to be humble. Even if you make all of the right decisions sometimes things will still go wrong. And sometimes, you may make errors without causing harm. And sometimes, the patient will get better no matter what you do.

"Search satisfaction" = the error of being satisfied by the first diagnosis that springs to mind

Lateral thinking = creativity + imagination = expanding the differential diagnosis list

Play a game with yourself, What else can it be? can you expand the DD to 3 things or 10? Never settle for the first obvious conclusion, without double checking.

Commission bias = it is better to be seen to do something, rather than nothing

"Don't just do something, stand there"

Educationalists often like to explain medical decision making by saying it involves "Bayesian" probabilities. However, that only works if much of the data is routinely known whereas most of medicine is not that simple.

Medicine involves statistics, decision trees and rational, logical thinking. But flow charts don't always fit the patient in front of you and sometimes, the statistics aren't known. So a clinician has to balance risk, uncertainty over the diagnosis and uncertainty over the correct treatment plan and then explain this uncertainty to the patient or confidently bluff a plan.

In medical research, a treatment decision reached by logic and then trialled through an RCT, can turn out to be "wrong" and to harm patients. This is because our logic doesn't always apply to biology or we do not understand enough of the biology to make the right logical deduction. Again, showing that we must be humble and accept that there are “known unknowns” and “unknown unknowns” and clinical uncertainty.

In the modern healthservice in the UK or similar country, clinicians and staff are seen as interchangable cogs within the machine. Not enough thought is given to variation between people and practice.

Different clinicians' personalities means they will interact with different patients' personalities. Not all patients will have success with all clinicians.

Medical decision making involves emotion as well as logic. It is important to reflect on how your emotions affect your judgement. Especially if you find a particular type of presentation or patient challenging. Have you let your emotion cloud your judgement?

A common mistake is to think that "gate keepers" or primary care physicians or GPs, are "entry level" clinicians who work "below" a specialist consultant. But in fact, a GP works very differently, managing risk and trying to allocate patients to the best pathway. They have to look after limited resources, treat those with "minor conditions" and ensure those patients with something serious get the approprate tests and reviews. Like finding a needle in a haystack. Which is very different to a specialist who has to process a needle in a conveyorbelt of needles.

knowing what you don't know is an essential skill in medicine.

Heuristics = essential knowledge = short cuts in thinking

Sometimes these short cuts are useful and important, but it is essential to know that you are taking the short cut, so that if you go wrong, you can find your way back and following the other route.

The bellcurve of health, ideally we as clinicians want to push as many patients to the healthy side as possible.